SAN JOSE, Calif. — Solar panels are on the rise for microgrids that bring electricity to small villages in the developing world, spawning work on low-power, direct-current homes, according to presentations at a conference here.

“In India, there’s been a big mindset shift among regulators and utilities in favor of photovoltaics and microgrids,” said Vineeth Vijayaraghavan, director of research and outreach for the non-profit Solarillion Foundation.

“So far, there’s been little research in networking microgrids, but the government is interested” in ways to connect DC rural grids to each other and to the AC urban grid, he said in a talk at the IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference.

The recent meeting between India’s new prime minister and the US president also included an agreement to step up research on low-power homes. Five research institutions each in the US and India will collaborate on the design of a 30 to 40 W home that can include at least one LED light, a brushless DC fan, a 12 W cellphone charger, a 23-inch TV, and a 10 W kitchen device with a motor, said Vijayaraghavan.

Researchers have been working on prototypes of such simple homes for some time. They hope India could provide a seed market for the highly efficient products that could then spread to other parts of rural Asia and Africa, he said.

The market for solar water pumps is also surging, he added, with as many as 40,000 now installed in India.

More research is needed in low power homes and in ways to connect DC solar microgrids to AC utilities, said Vineeth Vijayaraghavan.

More research is needed in low power homes and in ways to connect DC solar microgrids to AC utilities, said Vineeth Vijayaraghavan.

The Indian government is currently giving 30 to 100 percent subsidies for solar microgrids depending on how long it expects it to take to deploy the grid to the area, Solar is beginning to fill a gap from biomass microgrids, which have largely failed, said Vijayaraghavan.

In an indication of the trend, India’s largest biomass microgrid company, Husk Power Systems, has decided to shift to solar. Three quarters of its 84 plants are not operating today, largely because the promise of free feedstock has largely disappeared as farmers sell their waste to high bidders such as paper plants, he said.

Several speakers at the event said solar is on the rise in Africa and elsewhere, in part due to the falling costs of panels. As much as 20 percent of the world’s population -- about 1.5 billion people -- have no access to electricity.

“The reality is 400 million people have no access to electricity in India, and the figure jumps to as much as 600 to 700 million if you add those with only intermittent access,” Vijayaraghavan told the audience.

Currently fewer than a thousand solar microgrids operate in India, each serving 300 to 5,000 people. The country could use more than 300,000 of them to reach all its villages, he estimates.

Solar microgrids also are becoming commonplace in places such as Africa where Intel sends volunteer employees to set up PCs in schools and clinics and has a partnership with Solar City.

“They are on the roof installing solar panels while we are in the lab installing PCs,” said Luke Filose, manager of the Intel Education Service Corps program that has sent 400 people to 20 countries. “Solar prices are coming down rapidly, and grid penetration still isn’t what it should be, and it isn’t moving fast enough.”

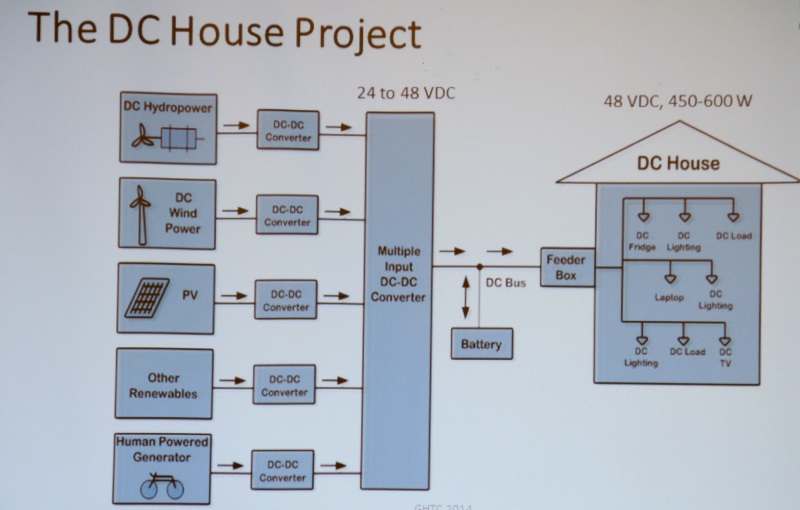

With all the new solar microgrids going up, a researcher at Cal Poly has proposed a design for a house using only the direct current that the panels produce, eliminating the waste of converting to and from alternating current.

The so-called DC House initially targets a 450-600 W home, with plans for a 150W version later. With solar microgrids on the rise, “it’s a good time for us to improve the technology to provide this kind of electricity in rural areas,” said Taufik, a professor specializing in power electronics and director of Cal Poly’s Electric Power Institute. (He uses a single name as is common in his native Indonesia.)

The junction box, initially just supporting 80 W, was the most challenging part of the design. The team has a 450 W version today and plans to work on a 600 W version with a single converter.

The team also created a smart wall plug. It can sense whatever output a device needs and step down from its native 48 V to between 3 to 24 V. Researchers also created a portable dimmable bulb with an embedded battery.

A shed on the Cal Poly campus served as the first prototype DC house in June. Taufik found a small abandoned home on the campus that will be the site for his first full system.

“Next year we plan to build DC houses on three campuses in Indonesia -- that is how I will spend my sabbatical,” said Taufik.

Requests for the design have already come in from Africa, Malaysia, and the Philippines shortly after the DC House website went live. “I had to turn them down as it will not be ready probably for another two or three years,” he said.

Among the group’s other designs, it is working on merry-go-rounds and swing sets that could generate energy

Several experts said the biggest issues they face are not about the technology

For instance, the wide variation in subsidy and donor levels creates very different business models. “The diversity is mind boggling… There are so many players it can be confusing,” said Vijayraghavan.

If people in one village being charged for electricity hear of people elsewhere for whom it is free, they resist. One village boycotted a solar microgrid because it used DC fans with an integrated switch rather than a switch on the wall. For the same reason, LED bulbs are now being designed to look like incandescent ones.

“Rural India does not want something urban India does not use -- it’s a problem of aspirations,” he said.

Creating self-sustaining ventures is key in a climate of diminishing grants. Like many non-profits, Community Solutions Initiative, a member of the IEEE, tries to spawn a local organization that runs and maintains the solar grids it installs, according to Ray Larsen, a Silicon Valley engineer who co-chairs the group.

“Silicon Valley caught on right away, saying, ‘that’s entrepreneurship, we get it,’ ” said Vijayaraghavan, noting efforts from Stanford and Santa Clara University.

“The traditional approach of getting someone to write a check or donate products is long gone,” said Intel's Filose, pointing to partnerships as the way forward.

“When you think of the challenges, I would describe it as a pretty bumpy, long, lonely road,” he said, quoting an African proverb: “If you want to go fast, go alone -- but if you want to go far, go together.”

— Rick Merritt, Silicon Valley Bureau Chief, EE Times

Source: EE Times

No comments:

Post a Comment